By Charlie Goldsmith

Charlie Goldsmith has been involved in the South Sudan education sector for fifteen years. He has overseen CGA Technologies assignments that have been pivotal in enacting positive change. Since 2014, pupil enrolment has tripled and girls’ enrolment has quadrupled. But 2m children still aren't in school. Here, Charlie sets out some proposals ahead of the 2022 academic year.

The challenge of the 2022 academic year and beyond: over 2m out of school

In 2021, South Sudan had 2.6m learners in education, of whom 49% were girls. Depending on perspective, this is either:

- A great result - getting close to 2020’s peak of 2.7m learners in education, which had grown from just 0.9m in 2014, and maintaining gains among girls in pre-COVID enrolment growth

- Not such a great result - breaking the trajectory of 15-20% year on year enrolment growth, with many boys dropping out between the two years

Whether you see the glass as half full or half empty, more than 2m school-age people in South Sudan are not in school. Since the ‘lowest-hanging fruit’ has already been harvested into education in the last seven years, fresh efforts will need to be exerted to get to where we ought to be, viz. at least twelve years of primary and secondary education for all.

This is both a generally relevant question to ask ourselves ahead of the 2022 academic year, and specifically important in the context of:

- Girls’ Education South Sudan becoming a de facto sector pooled fund, with U.K., Canadian and now U.S. funds coming into it and a “GESS3” due on stream in 2023

- Decision points for EU and various multilaterals

- A significantly increased host government budget for education, not yet matched by execution, with some recent improvements in execution of teacher remuneration funds, that will hopefully be sustained

1. Less fighting, pls

The cheapest and simplest way for enrolment, retention, attendance and attainment to improve is a reduction in conflict and for more locations to be, at minimum, conducive to access to education, and ideally welcoming. This is relevant not only to ‘faraway places of which we know little’ East of the Nile but to places like Yei and Kajo-Keji that were the ‘breadbasket’ of education enrolment pre-2016 – and indeed teacher production.

This is both an obvious statement and a slightly more subtle point in that many of those displaced within and beyond South Sudan in the conflicts of the last seven years have been engaging, whether as students or teachers, in education in the places they have been displaced to and, if given the opportunity to return to their places of origin, will give impetus to education there.

2. Although there are plenty of people available to teach and some are already good teachers, almost all could do more and/or better with some basic remuneration and support.

Almost 70,000 individuals have taught in South Sudan’s schools in the last five years. But intermittent and low remuneration, displacement, and more means that seldom have more than 45,000 been teaching at any one time – considerably fewer than are needed to teach reasonable class sizes for more than 2.7m pupils.

South Sudanese parents and learners are well aware that the chances of learning something are improved by learning in classes of fewer than 50 instead of in a group of 100 crammed in a room fit for 40. They will learn better in contexts where learners are getting a full day of lessons as opposed to a bit of teaching mid-morning.

The best should not be the enemy of the good. For the moment, South Sudan needs teachers on their feet, and lots of them, with access to a full set of materials, as set out below. Getting teachers teaching, most likely locally, is more urgent than trying to do anything complicated or prescriptive on qualifications or postings.

3. Money makes the system go round: teachers and key officials have to be remunerated somehow and the simpler, quicker and more predictable the flow, the better.

If teachers aren’t paid, they are financially unable to attend. If officials aren’t paid, they can scarcely be blamed for chasing per diems from international partners, rather than focusing on particularly strategic priorities.

Simplifying and speeding up flow of funds into the sector would be a major help. This applies to teacher remuneration, school grants and GESS cash transfers.

Up to 2012, rank and file teachers in South Sudan received monthly pay amounting to roundly $100. Recently, incentives that weren’t universal have been as little as $20 a month. Getting paid less than the $1.90 a day global poverty line in a land-locked, high-cost place had inevitable implications for output.

But the impact of EU-funded IMPACT incentives over the last four years has also been clear: even incentives worth as little as $20 a month, that were not delivered every month, got teachers attending and teaching in numbers (albeit few were teaching full timetables because they simply could not afford to).

School capitation grants for Acadmic Year 2021 were approved by GRSS in early 2021 but were not paid for most primaries. Getting them paid is a simple way for GRSS to show how it is supporting communities all across the country.

One opportunity for simplification could be to make teacher appointment and remuneration fully the responsibility of the schools and funded from a capitation grant – as it happens in the UK - with accountability for funds and outputs.

Feedback from families and schools is consistent that the earlier in the school year that girls’ cash transfers come, the more useful they are. The more reliably teacher remuneration and school grants flow, the less girls’ cash transfers will end up getting drawn upon for formal or informal school fees, and the more they will help the girls themselves.

4. Donors and partners come and go but ministry colleagues remain.

South Sudan’s monthly Education Transfers Monitoring Committee, now in its tenth year of operation, is a sustained example of regular and practical coordination between partners and government. It is also an example of the enduring and cumulative expertise of the MoEST team.

The cancellation less than a year in of a major partner education programme in 2021 was, for whatever reasons it occurred, a slightly less high point.

As more donors consolidate funds through GESS programmes and as GESS evolves towards being the sector pooled fund that was its original envisaged trajectory, there’s increased responsibility on both partners and the government to ensure good governance and accountability. The earlier and more MoGEI is involved in the design of programming, the better that it will likely go.

5. Low value cash transfers continue to work incredibly well for retention. It’s time to reinforce success of the model and remove barriers to the most marginalised.

GESS cash transfers, which CGA designed and set up with MoGEI in 2013-14, have been a runaway success. Our colleague Naomi Clugston’s 2018 paper Breaking Barriers to Girls' Education showed their disproportionate impact relative to value. GESS cash transfers are the distinguishing factor in evidence from 2021 enrolment where girls’ secondary enrolment held up while boys’ did not.

Cash transfers have had the same P5-S4 girls scope for seven years now. They continue to be implemented much the same way through one-off, ultra-low value payments paid ‘cash over the table’.

It’s time to reinforce success, not least by:

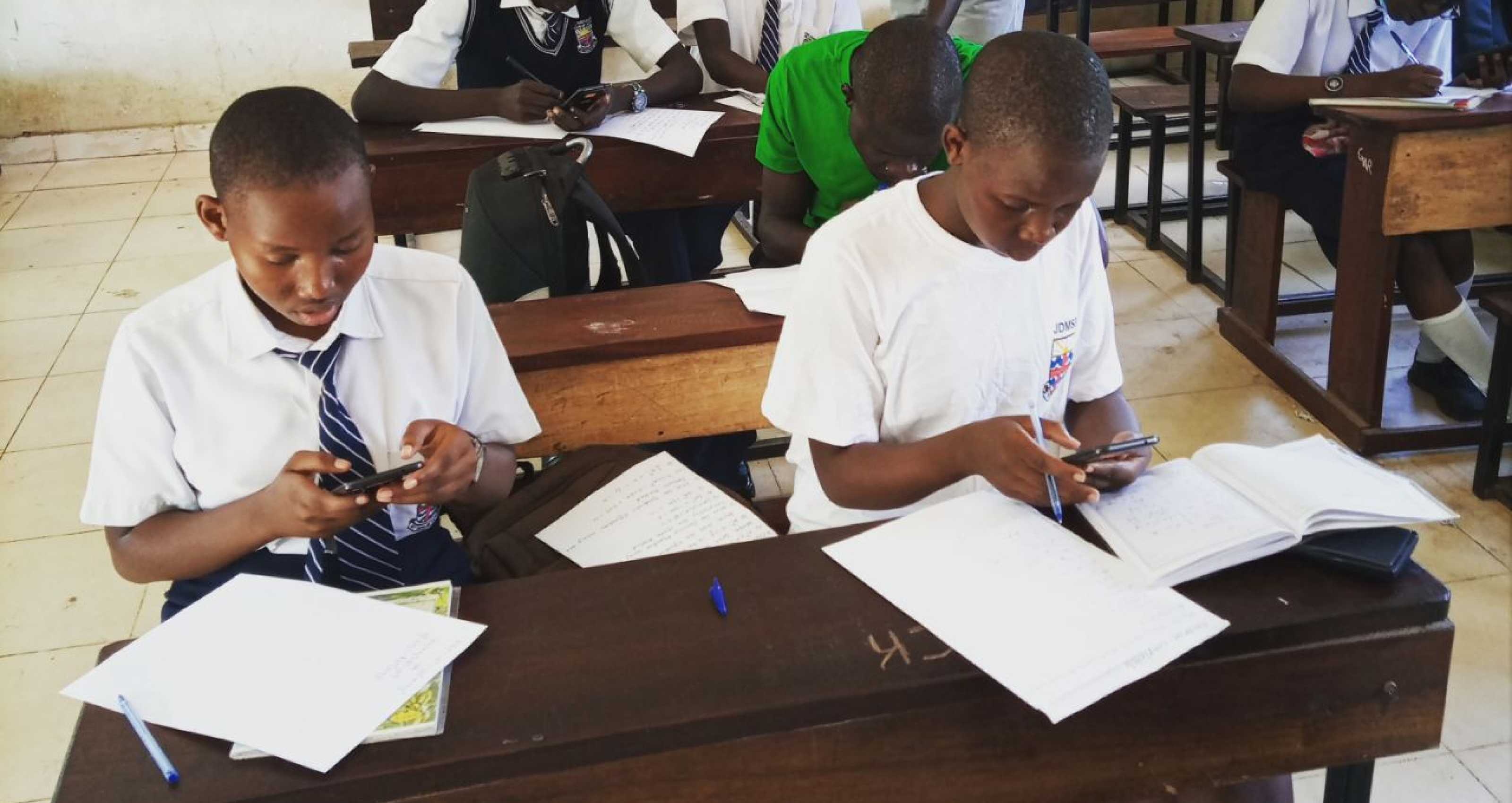

- Transitioning to e-payments (mobile banking/mobile money) and creating access to SIMs and handsets. This should not only improve value for money but it should ensure that girls and women in P5-S4 have access to at least basic devices that can be used to get digital education materials.

- Adding top-ups for the most marginalised girls and women, to whom the current flat rates don’t offer enough support to make the difference they need.

- Including vulnerable boys through a simple, categorical, non-stigmatising approach

- Streamlining arrangements about school fees in order for schools, learners, families and the government to be able to plan transparently and honestly.

- Joining up education cash transfers and the new social safety net so that those who stay committed to education can be confident that they will be supported.

To make these suggestions work, GRSS needs to make a specific, comprehensive and inclusive policy about out-of-school children and then implement it.

6. Supply has been ‘sweated’. A well-planned frugal expansion could deliver high value for limited outlay.

In 2014, South Sudan had just over 3,000 schools open. In 2021, without any major school construction programme, it had 5,850 schools open. Some of those schools are co-located, for example, a pre-school co-located with a primary school or a secondary school added when a primary school had reached a critical mass of primary leavers.

Supply has grown and responded to demand. Average enrolment per school has gone from barely 300 pupils to close to 500.

There are plenty of cautionary tales from within South Sudan, and from elsewhere on the continent, about expensive, unsustainable or politically-placed schools.

But now there is a clear need and a case in terms of state legitimacy for:

- At least one secondary school in every county with every payam (administrative division) able to access a secondary school.

- Additional primary school provision in ‘school deserts’. For example, the EPRR programme had more than 20 schools effectively ‘shovel-ready’ in 2021 at a price tag of just $75k per four-classroom starter school. Let’s get those and more built.

- Advances in using GIS for frugal school siting that build on work done by the Government of Sierra Leone. Combined with support from our friends at FabInc, this would make it possible to site and build much more efficiently than was formerly possible.

7. Promoting the availability and utilization of digital materials is a reliable way to improve access, retention and raise the floor on quality

Over fifteen years, there’s been limited evidence in South Sudan that high-polish model implementations have delivered sustainable impact on learning beyond the schools in question – and, in some cases, not even within them – proportionate to the investments made.

But there are things you can do for learning that are low cost and highly reliable. These build on what MoGEI and the Canadian-funded AGENCI programme team have done in the last year with frugal digital materials by ensuring every teacher and learner has access to the curriculum, the syllabi and a full set of textbooks. In 2021, MoGEI nobly made its 184 copyrighted textbooks available digitally free of charge to all South Sudanese users. The squeaks of joy about having a complete set of textbooks every time we set up a new county teacher Whatsapp group are pretty satisfying.

There’s no need for turning teachers into robots. But every teacher who has the core materials in their hands is a teacher with a start they haven’t formerly had – and if those are then complemented by other resources, scaffolding, support and so on provided digitally, so much the better.

If, as in section 6 above, you systematically build up students’ digital access, you can go even further – both with sharing materials digitally and with the exciting things like the “Colet Mentoring” app through which pupils at Juba Diocesan Model Secondary School access real-time homework support from student mentors at London’s St Paul’s School.

8. Qualifications and structure need tuning up: the jump from the South Sudan school certificate direct to tertiary qualifications is counterproductively big and drives a ‘brain drain’. There is now sufficient demand for it to be addressed.

The South Sudan Certificate and its Sudanese predecessor have a long history that it is worth building on. But:

- Communities, parents, learners and teachers are all expressing concerns about the value and relevance of the strong focus on memory-recall in the South SudanCertificate exam.

- In the absence of a recognised South Sudanese qualification between School Certificate and university, learners cannot ‘bank’ their efforts. This creates a brain drain of able and motivated students to Uganda to follow curricula through to A-Level in order to be able to access more academic university courses such as medicine.

- In some cases, these learners shift at S2 or earlier. The South Sudan system is the poorer for the absence of these students and the resources that follow them out of the country – students and resources that often both go out and stay out. We can think of no other African country with such an early ‘brain drain’.

It is in the interests of the South Sudan system to offer a path beyond the South Sudan Certificate. This could be A-Levels, consistent with other systems in East Africa, or this could be a propaedeutic year as Catholic University of South Sudan offers as a bridge to higher study. It could be a revision of the South Sudan Certificate to better examine skills and thinking, rather than memory recall. And/or it could include a pragmatic/vocational path, ideally with a digital component, that would make a practical route to employment opportunities, financial inclusion and hopefully economic development.

9. Schools are community hubs and it is perfectly acceptable in South Sudan to be a school pupil in your twenties. Let’s make the most of both of these opportunities.

South Sudan is exceptional in the extent to which attendance at and participation in school of 15-29 year-olds is socially accepted and approved of, even though this might be perceived as ‘over-age’ in other contexts. South Sudan Schools’ Attendance Monitoring System (SSSAMS) data shows that as many as 0.9m learners 15 and over, making up 35% of the national total of 2.6m learners, were enrolled in schools in 2021.

‘Over-age’ enrolment is absolutely the norm. There are sensibly adapted accelerated learning and alternative education system programmes for older learners who need to catch up to get back in the mainstream.

In combination with cash transfers described above, we think there is a great opportunity to offer at-scale ‘catch-up’ that delivers, complements and reinforces school provision rather than setting up parallel arrangements. (Mundanely, this in principle offers synergies with the major investments made under previous management in the electrics at our house.)

Similarly, schools are an excellent setting – whether as part of formal education provision or as an on-site complement – for complementary interventions in health, sexual and reproductive health and rights, employability and youth volunteering (not least building on the “Teach First/Teach For...” model).

We understand why international partners want to address youth specifically and we share their concern. However, we also think the synergies with general education can sometimes get a bit lost and are substantial. They are worth (re)discovering.

The Path to 4m

It’s AFCON at the moment and that’s often a good time to make progress in South Sudan because there is less fighting in the dry season. It is not impossible to make progress on the above points before school and rains start. As an education sector, let’s challenge ourselves to make the 2022 academic year in South Sudan a 3.2m learner year and then South Sudan’s first 4m learner year in the 2023 academic year.

Charlie Goldsmith first came to South Sudan in 2006, working for the Episcopal Church of (South) Sudan, helping to set up Juba Diocesan Model Secondary School. He lived in South Sudan until 2011, led the design and set-up of the www.sssams.org real-time education data system, national school grants, cash transfers and teacher incentives under the DFID-funded GESS1 programme. He has continued to oversee CGA Technologies’ work supporting the Ministry of General Education and Instruction, and driving enrolment, retention and achievement. Currently, Charlie is involved in CGA’s South Sudan work funded by Global Affairs Canada, UNICEF and Save the Children.

The views expressed here are his own.